Welcome to this sonic journey

Reading Responses

This semester, I have been tasked to write a number of responses to readings that we will be completing throughout the next few weeks.

-

9/17/2023

In this week's readings, I will delve into the profound insights offered by Mark Grimshaw and Tom Garner in their work, "Sonic Virtuality." The text proved to be a rich source of knowledge, shedding light on the multifaceted nature of sound. What particularly piqued my interest was the extensive exploration of the philosophical underpinnings of sound, which transcends the mere description of sound waves and delves into its profound significance.

One of the most captivating aspects of the text was the consideration of whether sound can exist independently, even if it remains uninterpreted by a conscious observer. This concept evoked a vivid memory from my past summer at the Notting Hill Carnival in London. Amidst the exuberant crowd and booming speakers, I vividly recall not just hearing the sound but feeling it resonating throughout my entire being. The bass reverberated through my body, highlighting that sound isn't merely an auditory experience; it's a visceral one. This experience underscored the intricate relationship between sound and perception, prompting questions about whether sound can truly be divorced from its association with objects.

Interestingly, when we encounter a sound, our minds often seek to connect it with an object or source. However, this dynamic shifts when we immerse ourselves in the world of music. In music, the sound itself takes center stage, transcending the instruments that produce it. This inherent quality of sound speaks to its deeply rooted intersubjectivity, where interpretation and existence are shaped by our sensory experiences. In essence, sound is not an isolated phenomenon; it's an integral part of our perception, profoundly influenced by our sensory engagement.

The readings have left me pondering a myriad of intriguing questions. Can we truly recreate a sound to perfection? Is it possible to replicate the exact emotional and sensory experience tied to a particular sound? These inquiries delve into the heart of sonic virtuality and challenge us to explore the boundaries of our understanding of sound, perception, and the intricate interplay between them.

-

9/23/2023

In the second week of readings, I found further insight into the meaning of sound art. I felt that the reading “Defining Sound Art” by Laura Maes and Marc Leman, which in essence describes the criteria for sound art, to be massively helpful in bettering my understanding of the meaning of sound art. This reading did also still leave me with some questions. Some of which I posed in our class discussion. I found it to be fascinating to consider where a line can be drawn between music and sound art. In discussion, professor Miranda Hardy argued that the reading actually says that they are in and of the same thing. In providing all of this criteria there are just different levels of sound art present.

Upon holding this discussion with the class and professor Miranda Hardy, I was able to consider the different ways I internalise sound that I hear. For example, before listening to a song, I often unconsciously queue myself to listen to sound compositions that are played by magnificent orchestras or talented bands that are intended to be appealing to my ear. In many of the sounds we have listened to thus far in the class, this has not been the case. The sounds at times have been jarring to the ear and feels at times like somebody is just interrupting music with their own idea of art. To this point, I need to attune my ear to be more receptive to this type of art and diverge from my usual passive listening experience with music. I believe I need to be more attentive to the sounds being created and therefore hold a greater appreciation for sound art altogether.

At the end of class I held an insightful discussion regarding this matter. More specifically, we discussed how this listening experience reminded me of my first experience watching a Jean Renoir film. On a first viewing without any foreknowledge of the many impressive techniques for cinematography that he applies to his filmmaking it was hard to appreciate the beauty of his art. Having spent an entire semester delving into his many pieces of art, I now hold a much greater appreciation for the masterpieces he was able to create and how he developed throughout his directorial career. I hope that I will find a similar insight for sound art in this class, where I will be able to use the “Defining Sound Art” to identify sound art and appreciate the sounds for their artistic value.

-

9/30/2023

In summary, the article, “Studio for Electronic Music: Why was the German recording facility so innovative?”, commemorates the 66th anniversary of the Studio for Electronic Music, established in Cologne, Germany, in 1951. This studio is considered the first modern music studio and was known for pushing the boundaries of electronically-synthesized sound. Founded during the Cold War by composers Werner Meyer-Eppler, Robert Beyer, and Herbert Eimert, it boasted state-of-the-art equipment and introduced unfamiliar instruments like the Monochord and Melochord, precursors to today's synthesizers. The studio influenced prominent artists like Karlheinz Stockhausen and paved the way for krautrock bands such as Kraftwerk and CAN, as well as modern dance, house, and trance music.

The Studio for Electronic Music's 66th anniversary celebrated in today's Google Doodle reminds us of its pioneering role in the world of music. Founded in the midst of the Cold War, this studio was a hub for experimentation with electronically-synthesized sound. It not only provided a platform for renowned composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen but also influenced a range of music genres, from krautrock to modern electronic dance music.

The fact that the studio introduced groundbreaking instruments like the Monochord and Melochord, which served as precursors to today's synthesizers, highlights its significance in the evolution of music technology. Its willingness to embrace innovation and push artistic boundaries made it a creative haven for musicians and composers.

This celebration is a testament to the enduring impact of the Studio for Electronic Music, which continues to resonate in contemporary music. It serves as a reminder of how experimentation and creativity can shape the course of musical history and inspire generations of artists.

-

16/30/2023

In the “From Epistemology to Creativity“ reading by Barry Truax, the author delves into the epistemological foundations of sound studies, aiming to answer the fundamental question of how we come to understand and interpret auditory experiences. The author proposes a model composed of two intertwined perceptual and cognitive processes, highlighting the complexity of sound's meaning-making. The first process involves a listener's ability to discern patterns and structures in sounds, ranging from micro-level sound variations to more extended rhythmic patterns. The study of psychoacoustics is instrumental in unraveling these intricate processes, which include aspects like pitch recognition, auditory stream formation, and the perception of acoustic space.

The second facet of this model is the role of contextual knowledge in sound interpretation, which stems from our lived experiences. This contextual knowledge encompasses identifying sound sources and their causal connections, as well as the sociocultural meanings attributed to these auditory encounters. The author terms this accumulated knowledge "soundscape competence," emphasizing that it continually evolves throughout our lives, both as shared knowledge and personal expertise.

The author underscores the interplay and interaction between these two processes, which are applicable to various domains, including language, music, and everyday environmental sounds. The blending of domains is further magnified in contemporary electroacoustic experiences, where technology permits the coexistence of amplified music within soundscapes, offering new compositional possibilities. As a practitioner in electroacoustic technology, the author utilizes this blend of inner and outer complexity to create soundscape compositions. These compositions draw upon the richness of the sounds themselves, invoking the listener's knowledge of specific contexts, and emphasizing how digital technology can bridge the gap between abstract sound constructions and lived experiences.

The text provides valuable insights for anyone working with sound, underlining the significance of contextual knowledge in sound composition and design. It challenges practitioners to engage with the intricacies of both the inner structure of sounds and the broader world they inhabit, fostering a deeper connection between the artistic and the everyday, and ultimately, pushing the boundaries of creative sound design and composition. This reading serves as a reminder of the profound relationship between sound, technology, and human experience in the context of modern sound studies.

-

31/30/2023

“Field Recording Centred Composition Practices” by John Levack Drever presents a compelling discourse on the metamorphosis of sound recording techniques, elucidating the complex transition from historic open reel recording systems to contemporary, sophisticated paraphernalia for capturing sounds. The author’s expressive narrative style explores the dichotomies embedded in contemporary sound recording practices and the social implications intertwined within the act of field recording.

Drever describes his array of advanced sound recording equipment, portraying it as a "bionic auditory prosthesis." This technology offers an unprecedented level of control over soundscapes, expanding the auditory senses while maintaining a distance between the recorder and the recorded environment. Drever provocatively contrasts modern gadgetry with historic methodologies, echoing John Gray's experiences with a massive Uher recorder and their role during a mountaineering recording adventure in the 1950s. This comparison evokes a sense of how technology has evolved, transforming the field of sound recording.

Drever further explores the paradoxical consequence of advanced sound recording techniques. While enhancing the aural capability, these gadgets create a barrier between the recorder and the authentic soundscape, fostering detachment and social separation. This echoes Hildegard Westerkamp's musings on the dichotomy between the recorder’s sense of access and their intrinsic separation from the surroundings. Drever artfully weaves in existential reflections about the challenges of recording technology leading to detachment, a sense of foreignness, and even a potential intrusion.

Drever poses a series of profound questions, which compel me to contemplate the ethical and practical dimensions of field recording. These queries navigate the purpose, ethics, and approach of recording: from the selection of sound sources to navigating the thin line between passive observation and active interference. In this complex web of inquiries, the text highlights the intricate balance between the recorder's technological prowess and their ethical responsibility towards the soundscape.

Reflecting upon this text in the context of my own practice, I recognise the evolving nature of technology in the field of sound recording. It underscores the delicate interplay between technological advancement and the ethical implications that demand introspection in my creative work. This text challenges my understanding of the fine line between active participation and passive observation in the act of field recording, prompting me to consider the ethical responsibility of the recorder in shaping the auditory landscape. It serves as a catalyst to explore new approaches, placing emphasis on a balanced and conscientious use of technology in sound capture while maintaining respect for the natural acoustics and their contexts.

Sound Library

Sound Library

Listen up.

9/19/2023

Here is a collection of the tracks that I have complied thus far.

Organising System

Exercise Two

Exercise Two Audio

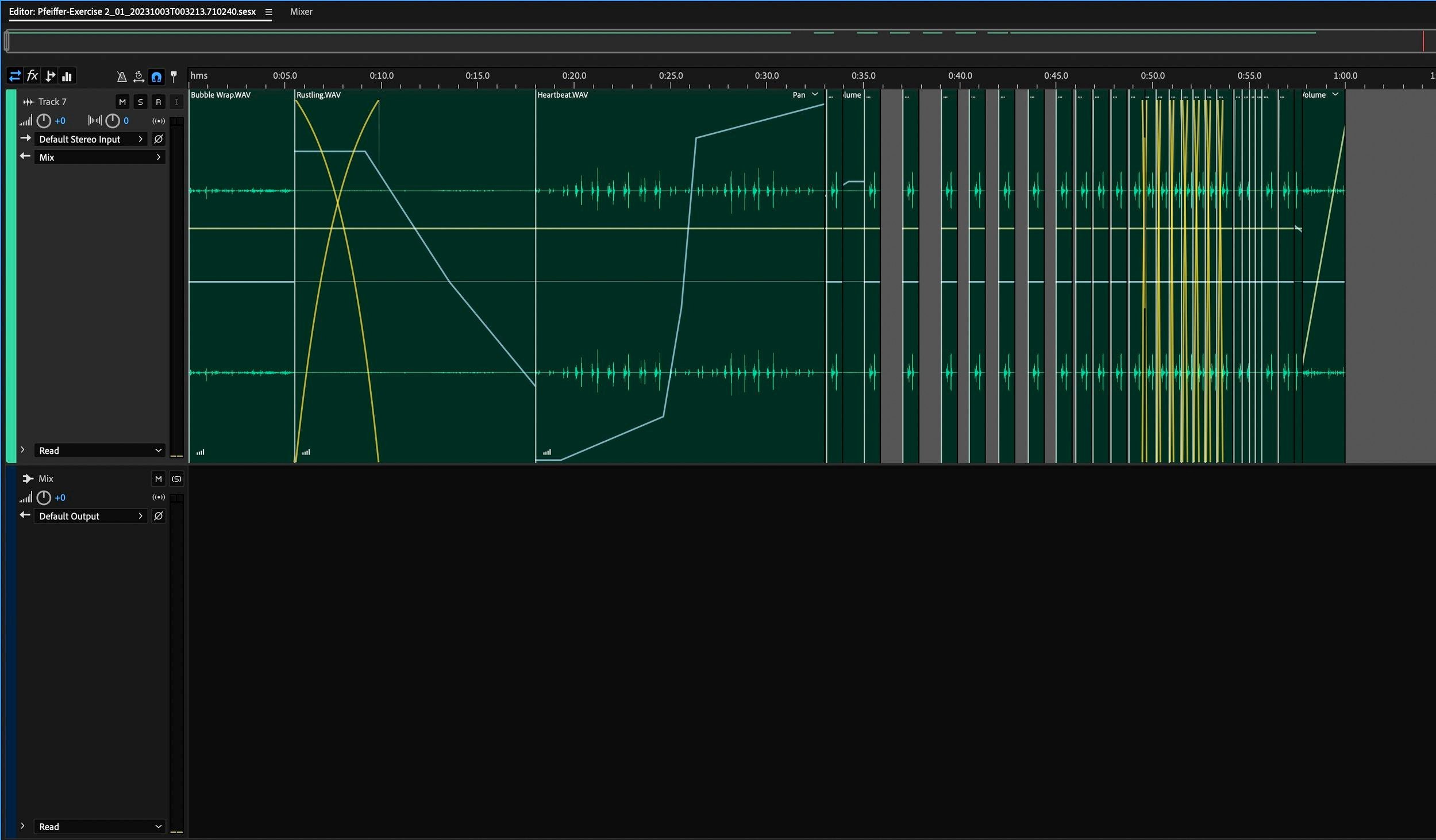

Attached is the audio where I have spliced three sounds together to create my 1-minute horizontal single-track .

Voice Project

This piece is titled “Transhumanism”. This is a voice project I created by using each individual recording that was captured by our sound class, and I was able to combine them to make sound art that is composed only of the human voice. As a result, this mix is composed of 14 separate tracks. As the piece progresses the sound begins to become less decipherable as the human voice, until the only human voice that has thread through the piece chanting “sound” appears to no longer be human. This transformation is largely symbolic for the future of humanity and the idea of transhumanism.

Polaroid Stories Interlude

Final Project